The lack of a common health data language has been ‘the elephant in the room’ for a very long time. Unfortunately, very few people acknowledge the need for a clinical lingua franca as a critical foundation for eHealth. The mainstream view seems to be that messages are/will be enough and that creating a standard language for health information is either too hard or too complicated. Is it really that hard? Or is that just the view of those with vested interest in perpetuating the message paradigm?

"Smart data, smarter healthcare"

Adverse reaction risk: provenance

Recording adverse reactions, allergies and intolerances to medications and other substances is universally regarded as a high priority for clinical safety. This is the ‘Adverse reaction risk’ archetype’s story - an international, cross SDO collaboration that achieved consensus. It demonstrates the potential value that comes if we choose to work together, rather than create more silos.

Bridging the interop chasms

Incoherence ain't all bad!

Incoherence is not ideal, but it is a realistic part of any work such as we are doing within the openEHR community. Transparency and openness can mitigate some of the incoherence. Within a transparent, governed and collaborative environment incoherence and apparent conflict can be recognised and leveraged constructively to improve the quality of archetypes.

Case Study: Clinical Engagement

Bridging the gap between the clinical experts and software engineers involved in eHealth projects is well known for being difficult and frustrating for both sides. The openEHR methodology is having great success in bringing the non-technical clinicians along with us on the clinical modelling journey.

Brazilian EHR innovation, powered by openEHR

The challenge for FHIR: meeting real world clinician requirements

With the increasing burden of technical engagement resulting from the incredible expectations generated by FHIR globally, perhaps the clinical content specification should be outsourced to... the clinicians first of all, ensuring that the clinical content can be represented in a technical format for implementation.

EHR building blocks

For many years I have borrowed an analogy using Lego building blocks rather than the notion of generic 'shapes' - that if we get the foundation building blocks agreed and fit for use in our EHRs (ie clinical archetypes), then they can be re-used in multiple contexts and combined in any permutation or combination to represent the clinical documentation that we need.

Clinical modelling, openEHR style

The outcome of a program of coordinated clinical content standardisation provides a long term and sustainable national approach to developing, maintaining and governing jurisdictional health data specifications. It can form the backbone for a national health data strategy and is a key way to ensure that clinicians contribute their expertise to jurisdictional eHealth programs.

Inaugural joint archetype review by HL7 & openEHR!

#Uncomplexication of Clinical Infostructure

My presentation delivered remotely from Australia to the Arctic Conference on Dual-Model based Clinical Decision Support & Knowledge Management in Tromsø, Norway today.

The Archetype 'Elevator Pitch'

The Questionnaire Challenge

How should we model questionnaires in our health data? This is something that @ianmcnicoll and I have grappled with for years. We have reached a conclusion in recent times, and our approach, perhaps rather controversially, is not to model them! Yes, you read me right - as a general principle, don't archetype questionnaires.

Now of course there will be some situations where there are standardised and ubiquitous questionnaires and perhaps it will be reasonable to lock these down as fixed data elements and value sets in an archetype, and maybe even govern them within a CKM environment.

But... Consider the number of questionnaires out 'in the wild' at any point in time. Should each of these be archetyped?

Let's think it through. If there are 5000 questionnaires in the world (and clearly there are way more questionnaires than that out in the health ecosystem) then we would need a corresponding whopping 5000 archetypes. And, as we all know, no two questionnaires will be alike even if they have a common parent document - it is always human nature to 'tweak' each one for local use because 'our situation' is unique. It's just the way it is. The consequences are that any data captured using the myriad of archetypes, even though they may be similar, the data will not be interoperable. We will have a huge number of archetypes with a huge variation in content and intent - not a lot of upside from my point of view.

Another alternative could be to define a generic archetype pattern for a questionnaire, and re-use that. In fact we tried this back in 2007 with our work in the NHS - you can see a reasonable example here. The resulting questionnaire pattern is pretty simple and relies on using the templating layer to document the questions, and either templating or use of a terminology subset to record the answers. The equivalent FHIR resource appears similar in principle and intended use. This kind of pattern provides a common framework for a questionnaire but really doesn't give us a lot more interoperability for questionnaire data - the actual questionnaire content will vary enormously and the results can still be chaotic.

So, still somewhat clunky and awkward - not an elegant solution at all.

Then we got to thinking: Do we always need to actually record the questions and their answers in the EHR? This is a critical question. Sometimes the answer is yes, but most often I think we will find that we don't need to record the actual question and (often) check box response. What we really want to record is the outcome, the real health information meaning.

Think about the practical aspects of this...

Clinicians have a systematic questioning process for history taking - we all have a similar pattern but ask subtly different questions - resulting in zillions of permutations and combinations and levels of granularity. Questions could range from: "Have you had any abdominal symptoms?" to "Have you had any nausea, vomiting, reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation etc" to whatever combination is relevant for a given clinician in a given clinical situation. Many will ask the same kind of question slightly differently. Every resulting questionnaire will be slightly different.

And what do they record? They don't record each question and corresponding Yes/No answers in their paper health records. They record the positive responses or the relevant negatives, and/or maybe a quick note that there were no positive responses to systematic questioning about current symptoms, problems, past history, family history etc.

So we need to ask ourselves: Do we need to record the exact question, the potential alternative answers and the actual answer?

If the answer is yes, then it is a very good reason to lock in the questionnaire in an archetype, or at least a template.

If the answer is no, then what is the best way to record the relevant data - the relevant positives and the relevant negatives. For example, with abdominal pain - record the details about their diarrhoea and colicky pain in the right lower abdomen, PLUS that the patient has NEVER had an Appendicectomy.

So I'm suggesting that we need to record the positive presence of something identified in the questionnaire, for example a symptom, diagnosis or previous procedure, and the positive absence of related things. In this case, record the details about the diarrhoea and abdominal pain as the positive presence of symptoms using the Symptom archetype and positive exclusion of a previous Appendicectomy procedure in the Exclusion of Procedure archetype. We don't need to record the actual question and corresponding Yes/No answer.

So our current approach in Ocean is to use the software UI as the means to display the checklist or questionnaire, but only record in the electronic health record any relevant answers - both the positive presence of symptoms, signs, diagnoses, procedures and tests etc, and also the positive exclusion of any of these things - all using standardised archetypes.

Lets face it, it is not often that we ever go back to look at the raw questionnaire data again. So now we tend not to record the raw data (with some exceptions, where it may be required or useful) but use a transform so that a patient's or clinician's positive tick in a box for 'Past History of Epilepsy?' will be converted into a positive statement of 'Epilepsy' within an EHR, using the Diagnosis archetype. Any additional 'other' free text or 'details' or 'date of diagnosis' from the questionnaire can be captured using other relevant data fields for the Diagnosis archetype. The benefit from this approach is that this data can then be potentially re-used into the future as part of a comprehensive Problem List, not just buried as a ticked check box within a questionnaire from years ago, perhaps never to see the light of day ever again.

Consider the questionnaire as what it really is - just a clinical communication tool, a checklist. It is absolutely not the best means to record, persist and re-use good quality health data. What we really want to record in a consistent way are those critical pieces of health information in a formal archetype so that the data can be utilised for long term health records, decision support, exchange or analysis. Recording the check boxes answers from a questionnaire don't really do that job!

Archetypes in the Real World

I've spent the past week in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Ian McNicoll (@ianmcnicoll) and I were been training clinicians about archetypes and clinical knowledge governance, ready for the launch of their national CKM. A highlight was a side trip to visit the state-of-the-art Paediatric Intensive Care Unit in Ljubljana. The electronic health record has been running there now for two years, with electronic processes gradually taking over. I was escorted by the clinician in charge of the ICU, Professor Kalan. The purpose of the visit – for him to meet someone who facilitated the archetypes used to run his EHR and for me to see our collective international archetype work implemented and used for real clinical purposes, largely under the expert clinical informatics guidance from Ian.

I was thrilled and a little taken aback, all at once. It is one thing to sit in an office researching clinical models and then to remotely collaborate with our international archetype community. But it is another to see real-time data being collected half a world away from home and knowing that we all had a small part in this, especially to support such critical care for a newborn baby. In the photo, above, you might just be able to spot a humidicrib surrounded by all of the equipment.

The majority of these archetypes were built by the international openEHR community for various projects and now utilised under the CC-BY-SA license by the EHR company to develop their clinical system. There are some local archetypes in use as well – added for practical and pragmatic purposes - but these are very much in the minority. These same international archetypes are also being used in the EHR repository in the Northern Territory, Australia, and are underpinning their current work on shared antenatal care and hearing health programs. Soon this work is to be extended for renal failure and heart disease. And across more than 20 sites in Australia we have an infection control system that is using both archetypes and some that have been built specifically to support infection control activities and outbreak management. These shared archetypes are also underpinning work in UK, Brazil, Japan and Sweden.

Next week Ian and I are in Norway to support the Norwegian national archetype effort – training their clinicians and informaticians about archetypes, and especially governance principles at a national level.

There are now 5 CKMs in existence:

- the openEHR international CKM;

- Australia;

- City of Moscow;

- UK clinical community; and the brand new

- Slovenian eHealth program CKM.

The international CKM will continue to gather quality archetypes from all sources and coordinate international review and modelling activities. The intent is for this CKM to be the first port of call for those looking for an archetype.

The national-, organisation- or program-based CKMs will be focussed on supporting local health IT activities and will leverage the international pool of archetypes by a virtual 'read only' reference capability as well as hold specific local archetypes or modifications of the international archetypes that will support local implementation.

Above all the aim is to create high quality, computable, clinical content definitions that have been developed and ratified by the clinicians themselves. In turn this will support collection of good quality data that can be used for a variety of purposes – ranging from the health record itself; through querying and knowledge-based activities such as decision support; aggregation, analysis and research; and secondary use, including population health activities.

I have said it before, but let me say it again…

IT. IS. ALL. ABOUT. THE. DATA.

In the discussions about standards, the standardisation of data is usually missed.

Seeing this little baby in a humidicrib in amongst all of the 'machines that go beep' has invigorated me again.

Let's continue, and even accelerate, our collaboration on the development of archetypes. This will enable us to gather the data we need to provide the kind of healthcare our patients deserve.

Engaging clinicians: building EHR specifications

There is a methodology that is pragmatically evolving from my experience in openEHR clinical modelling work over the past few years. It has developed in a rather ad hoc way, and totally in response to working directly with clinicians. The simplicity and apparent effectiveness – both for me and the clinicians involved - continues to surprise me each time I use it. The clinical content specifications for specialised health records and care plans that we are building are being developed with a sequence of expert input and clinical verification:

- Identifying the clinical requirements and business rules in conjunction with a selected initial domain expert group;

- Broader abstract verification of the notion of ‘maximal data set’ for ‘universal use case’ during formal archetype review cycles;

- Contextual validation during template review by ‘on-the-ground’ clinicians; and finally, although to a lesser degree,

- Validation during mapping and migration of legacy data.

With each project I am refining this process. Starting off a project with face-to-face meetings has been a ‘no brainer’ – after all, it takes a while for everyone to understand the get the idea of what we are doing. However after initial workshops, pretty much everything else can be done via web conference, online collaboration via CKM and email.

I find the initial workshops are usually greatly satisfying. Within hours we can be creating two outputs – a mind map that reflects the clinicians evolving conversation about their requirements and, in parallel, an equally agile template of clinical content specifications that can be verified by the clinicians in real time.

The mind map is displayed on a shared screen or via a data projector and acts as a living document, evolving as we talk through the clinical requirements, and identify the complexities, dependencies and relationships of all the components. The final mind map may be surprisingly different to how it started, and at the end of the conversation, the clinicians can verify that what they’ve said if accurately reflected in the mind map. It is an open source tool, so we can also share this around after the workshop for further comments.

Most recently I have begun building a template on the fly during the workshop, using any existing archetypes that are available, and identifying gaps or the need for new archetypes on the mind map as we go. In this way we are actually building the content specification in front of the clinicians as well. They get an understanding of how the abstract discussion will actually shape the resulting EHR content and they can verify it as we gradually pull it together. The domain experts are immediately equipped to answer the question: “Does this specification match what you have been telling me you do in practice?”

This methodology seems to bring the clinicians along with us on the clinical modelling journey, and most are able to understand at least some of the implications of some of our requirements discussions and, in particular, the ‘shape’ of the data that we can collect. It is a process seems to suit the thinking process of many clinicians and the overwhelmingly consistent feedback from recent workshops is that they have all actually enjoyed the experience and want to know what are the next steps for them to be involved. So that’s certainly a winner.

And the funders/jurisdictions are anecdotally confirming for me that they are finding that this approach is supporting higher quality specifications in a much shorter time frame.

For example, at a project kickoff workshop for a new project recently, in two days we:

- developed a series of mind maps capturing a consensus view of the clinical requirements and business processes;

- identified all the archetypes required for the entire project, including those that existed and were ‘fit for use’, those that needed some extension to meet requirements and new archetypes that needed to be created;

- identified sources of information or mind mapped the requirements for each new archetype identified; and

- built 3 templates comprising all of the existing archetypes available from a number of sources – the NEHTA CKM http://dcm.nehta.org.au/ckm/, the openEHR international CKM http://www.openehr.org/ckm/ and local drafts that I had on my own computer. For a number of the new archetypes we also collectively identified source information that would inform or be the basis for the archetype development.

All of this described above took 8 medical practitioners clinicians away from their everyday practice for only 1-2 days, each according to their availability. Yet it provided the foundation for development of a new clinical application.

Then I go home. Next steps are to refine the mind map, modify/update/specialise any archetypes for which we have identified new requirements and build the new ones. And in parallel start the collaborative process through a CKM project to ensure that existing and modified archetypes are ‘fit for (our project’s) purpose’, and to upload and initiate reviews on the new draft archetypes.

All work to progress these archetypes to maturity (ie aiming for clinical consensus) and then validate the templates as ready for handover to the implementers can be done online, asynchronously and at a time convenient to the clinicians work/life balance!

I live over 2000 kilometres away from these clinicians. Yet the combination of web conference and CKM enables us to operate as an ongoing collaborative team. It seems to be working well at the moment... No doubt I'll continue to learn how to do it better.

The Archetype Journey...

I'm surprised to realise I've been building archetypes for over 7 years. It honestly doesn't feel that long. It still feels like we are in the relatively early days of understanding how to model clinical archetypes, to validate them and to govern them. I am learning more with each archetype I build. They are definitely getting better and the process more refined. But we aren't there yet. We have a ways to go! Let me try to share some idea of the challenges and complexities I see…

We can build all kinds of archetypes for different purposes.

There are the ones we just want to use for our own project or purpose, to be used in splendid isolation. Yes, anyone can build an archetype for any reason. Easy as. No design constraints, no collaboration, just whatever you want to model and as large or complex as you like.

But if you want to build them so that they will be re-used and shared, then a whole different approach is required. Each archetype needs to fit with the others around it, to complement but not duplicate or overlap; to be of the same granularity; to be consistent with the way similar concepts are modelled; to have the same principles regarding the level of detail modelled; the same approach to defining scope; and of course the same approach to defining a clinical concept versus a data element or group of data elements… The list goes on.

Some archetypes are straightforward to design and build, for example all the very prescriptive and well recognised scales like the Braden Scale or Glasgow Coma Scale. These are the 'no brainers' of clinical modelling.

Some are harder and more abstract, such as those underpinning a clinical decision support system of orders and activities to ensure that care plans are carried out, clinical outcomes achieved and patients don't 'fall through the cracks' from transitions of care.

Then there are the repositories of archetypes that are intended to work as single, cohesive pool of models – each archetype for a single clinical concept that all sits closely aligned to the next one, but minimising any duplication or overlap.

That is a massive coordination task, and one that I underestimated hugely when we embarked on the development of the openEHR Clinical Knowledge Manager, and especially more recently, the really active development and coordination required to manage the model development, collaboration and management process within the Australian CKM – where the national eHealth program and jurisdictions are working within the same domain of models, developing new ones for specific purposes and re-using common, shared models for different use cases and clinical contexts.

The archetype ecosystems are hard, numbers of archetypes that need to work together intimately and precisely to enable the accurate and safe modelling of clinical data. Physical examination is the perfect example that has been weighing on my mind now for some time. I've dabbled with small parts of this over the years, as specific projects needed to model a small part of the physical exam here and there. My initial focus was on modelling generic patterns for inspection, palpation, auscultation and percussion – four well identified pillars of the art of clinical examination. If you take a look at the Inspection archetype clinicians will recognise the kind of pattern that we were taught in First Year of our Medical or Nursing degrees. And I built huge mind maps to try to anticipate how the basic generic pattern could be specialised or adapted for use in all aspects of recording the inspection component of clinical examination. Over time, I have convinced myself that this would not work, and so the ongoing dilemma was how to approach it to create a standardised, yet extraordinarily flexible solution.

Over time, I have convinced myself that this would not work, and so the ongoing dilemma was how to approach it to create a standardised, yet extraordinarily flexible solution.

Consider the dilemma of modelling physical examination. How can we capture the fractal nature of physical examination? How can we represent the art of every clinician's practice in standardised archetypes? We need models that can be standardised, yet we also need to be able to respond to the massive variability in the requirements and approach of each and every clinician. Each profession will record the same concept in different levels of detail, and often in a slightly different context. Each specialty will record different combinations of details. Specialists need all the detail; generalists only want to record the bare basics, unless they find something significant in which case they want to drill down to the nth degree. And don't forget the ability to just quickly note 'NAD' as you fly past to the next part of the examination; for rheumatologists to record a homunculus; for the requirement for addition of photos or annotated diagrams! Ha – modelling physical examination IS NOT SIMPLE!

I think I might have finally broken the back of the physical examination modelling dilemma just this week. Seven years after starting this journey, with all this modelling experience behind me! The one sure thing I have learned – a realisation of how much we don't know. Don't let anyone tell you it is easy or we know enough. IMO we aren't ready to publish standards or even specifications about this work, yet. But we are making good, sound, robust progress. We can start to document our experience and sound principles.

This new domain of clinical knowledge management is complex; nobody should be saying we have it sorted...

Archetype Re-use

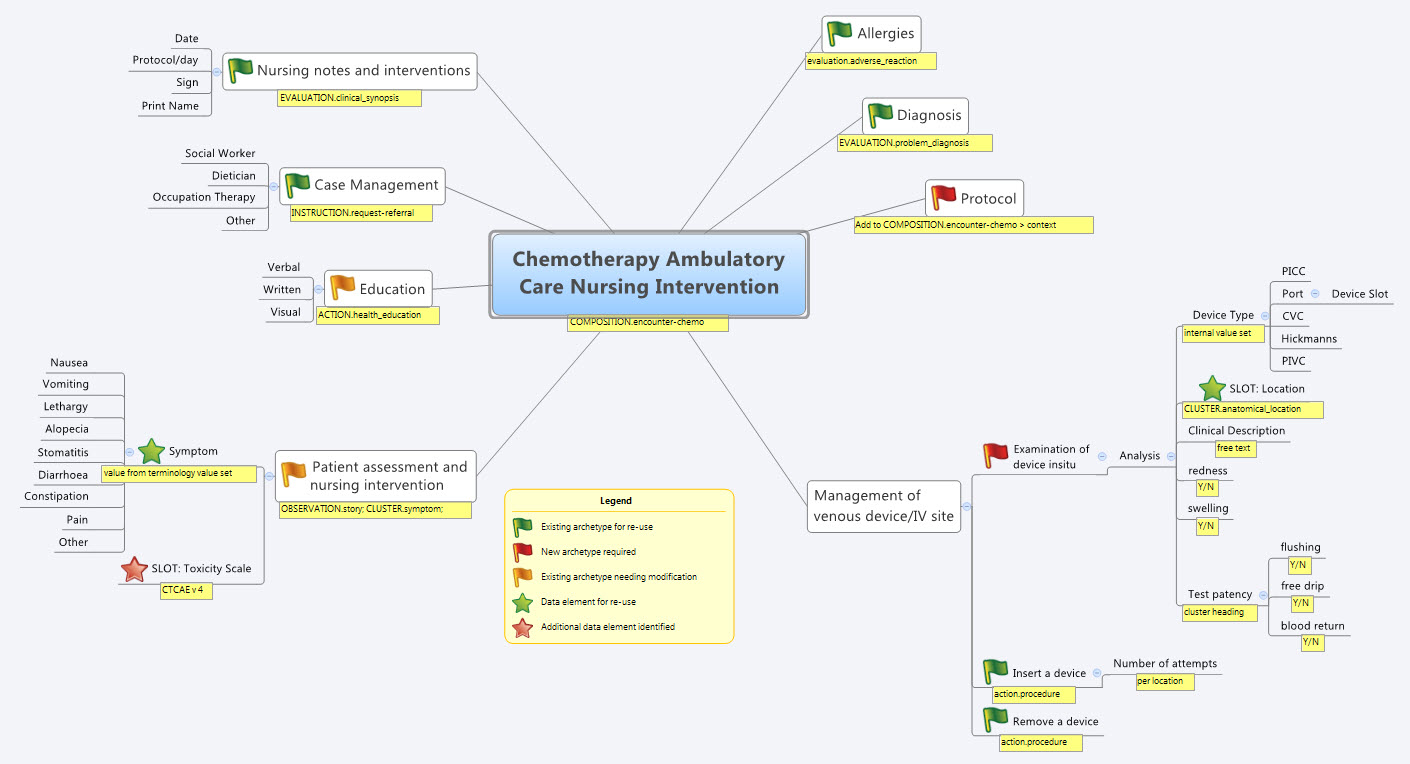

Last Thursday & Friday @hughleslie and I presented a two day training course on openEHR clinical modelling. Introductory training typically starts with a day to provide an overview – the "what, why, how" about openEHR, a demo of the clinical modelling methodology and tooling, followed by setting the context about where and how it is being used around the world. Day Two is usually aimed at putting away the theoretical powerpoints and getting everyone involved - hands on modelling. At the end of Day One I asked the trainees to select something they will need to model in coming months and set it as our challenge for the next day. We talked about the possibility health or discharge summaries – that's pretty easy as we largely have the quite mature content for these and other continuity of care documents. What they actually sent through was an Antineoplastic Drug Administration Checklist, a Chemotherapy Ambulatory Care Nursing Intervention and Antineoplastic Drug Patient Assessment Tool! Sounded rather daunting! Although all very relevant to this group and the content they will have to create for the new oncology EHR they are building.

Perusing the Drug Checklist ifrst - it was easily apparent it going to need template comprising mostly ACTION archetypes but it meant starting with some fairly advanced modelling which wasn't the intent as an initial learning exercise.. The Patient Assessment Tool, primarily a checklist, had its own tricky issues about what to persist sensibly in an EHR. So we decided to leave these two for Day Three or Four or..!

So our practical modelling task was to represent the Chemotherapy Ambulatory Care  Nursing Intervention form. The form had been sourced from another hospital as an example of an existing form and the initial part of the analysis involved working out the intent of the form .

Nursing Intervention form. The form had been sourced from another hospital as an example of an existing form and the initial part of the analysis involved working out the intent of the form .

What I've found over years is that we as human beings are very forgiving when it comes to filling out forms – no matter how bad they are, clinical staff still endeavour to fill them out as best they can, and usually do a pretty amazing job. How successful this is from a data point of view, is a matter for further debate and investigation, I guess. There is no doubt we have to do a better job when we try to represent these forms in electronic format.

We also discussed that this modelling and design process was an opportunity to streamline and refine workflow and records rather than perpetuating outmoded or inappropriate or plain wrong ways of doing things.

So, an outline of the openEHR modelling methodology as we used it:

- Mind map the domain – identify the scope and level of detail required for modelling (in this case, representing just one paper form)

- Identify:

- existing archetypes ready for re-use;

- existing archetypes requiring modification or specialisation; and

- new archetypes needing development

- Specialise existing archetypes – in this case COMPOSITION.encounter to COMPOSITION.encounter-chemo with the addition of the Protocol/Cycle/Day of Cycle to the context

- Modify existing archetypes – in this case we identified a new requirement for a SLOT to contain CTCAE archetypes (identical to the SLOT added to the EVALUATION.problem_diagnosis archetype for the same purpose). Now in a formal operational sense, we should specialise (and thus validly extend) the archetype for our local use, and submit a request to the governing body for our additional requirements to be added to the governed archetype as a backwards compatible revision.

- Build new archetypes – in this case, an OBSERVATION for recording the state of the inserted intravenous access device. Don't take too much notice of the content – we didn't nail this content as correct by any means, but it was enough for use as an exercise to understand how to transfer our collective mind map thoughts directly to the Archetype Editor.

- Build the template.

So by the end of the second day, the trainee modellers had worked through a real-life use-case including extended discussions about how to approach and analyse the data, and with their own hands were using the clinical modelling tooling to modify the existing, and create new, archetypes to suit their specific clinical purpose.

What surprised me, even after all this time and experience, was that even in a relatively 'new' domain, we already had the bulk of the archetypes defined and available in the NEHTA CKM. It just underlines the fact that standardised and clinically verified core clinical content can be re-used effectively time and time again in multiple clinical contexts.The only area in our modelling that was missing, in terms of content, was how to represent the nurses assessment of the IV device before administering chemo and that was not oncology specific but will be a universal nursing activity in any specialty or domain.

So what were we able to re-use from the NEHTA CKM?

- COMPOSITION.encounter

- EVALUATION.adverse_reaction – one instance per adverse reaction included in a adverse reaction list

- EVALUATION.clinical_synopsis

- EVALUATION.problem_diagnosis – one instance per diagnosis included in a problem list

- INSTRUCTION.request-referral – one instance per referral requested

- ACTION.health_education

- ACTION.procedure – with two instances for different purposes

…and now that we have a use-case we could consider requesting adding the following from the openEHR CKM to the NEHTA instance:

- OBSERVATION.story

- CLUSTER.symptom – with multiple instances for each symptom identified

And the major benefit from this methodology is that each archetype is freely available for use and re-use from a tightly governed library of models. This openEHR approach has been designed to specifically counter the traditional EHR development of locked-in, proprietary vendor data. An example of this problem is well explained in a timely and recent blog - The Stockholm Syndrome and EMRs! It is well worth a read. Increasingly, although not so obvious in the US, there is an increasing momentum and shift towards approaches that avoid health data lock-in and instead enable health information to be preserved, exchanged, aggregated, integrated and analysed in an open and non-proprietary format - this is liquid data; data that can flow.

Warts and all: Reviewing an archetype

During my visit to HIMSS12 in February, I finally met Jerry Fahrni (@JFahrni) face to face - a pharmacist and Twitter colleague I'd had 140 character conversations over some years. We'd also talked on Skype once about some of the clinical archetypes some time ago, and during our HIMSS conversation I managed to persuade him to take a look at the openEHR community's Adverse Reaction archetype and participate in the community review.

He did, and at my further request he has put ink to blog and has recorded his experience as a newbie reviewer so that others might have some sense of what completing an archetype review entails, warts and all.

Jerry's review, reproduced here:

...According to good ol’ Merriam-Webster an archetype is “the original pattern or model of which all things of the same type are representations or copies: also : a perfect example“. Simple enough, but still too vague for my brain so I went in search of a better explanation which I found at Heather’s blog – Archetypical.

According to the Archetypical site ”openEHR archetypes are computable definitions created by the clinical domain experts for each single discrete clinical concept – a maximal (rather than minimum) data-set designed for all use-cases and all stakeholders. For example, one archetype can describe all data, methods and situations required to capture a blood sugar measurement from a glucometer at home, during a clinical consultation, or when having a glucose tolerance test or challenge at the laboratory. Other archetypes enable us to record the details about a diagnosis or to order a medication. Each archetype is built to a ‘design once, re-use over and over again’ principle and, most important, the archetype outputs are structured and fully computable representations of the health information. They can be linked to clinical terminologies such as SNOMED-CT, allowing clinicians to document the health information unambiguously to support direct patient care. The maximal data-set notion underpinning archetypes ensures that data conforming to an archetype can be re-used in all related use-cases – from direct provision of clinical care through to a range of secondary uses.” That gave me a better understanding of what they were trying to do.

Anyway, when Heather asked me to review the Adverse Reaction archetype I was a little hesitant. The projects I’m asked to be involved with are typically much smaller in scale. This was something different and I felt a little intimidated. My gut reaction was to politely decline, but when someone asks you to do something face to face it makes excusing yourself for some lame reason a lot harder. So I agreed with more than a bit of trepidation.

The openEHR project utilizes a system called the Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM). In the most basic terms, the CKM is an online content management system for all the archetypes being designed by the openEHR project, and it’s impressive. A more in depth description can be found here.

Logging into the system was simple. The email invitation I received to review the Adverse Reaction Archetype contained a link that took me to the exact location I was supposed to be. From there things got a bit more complicated. The CKM is easy enough to navigate, but the amount of information and navigational elements within the system is staggering. It took me a while to figure out exactly what I was supposed to do. Once I figured it out I was able to quickly go through the archetype, read what other comments people had made and make a couple of minor notes myself. One thing I could never completely figure out was how to save my work in the middle and continue later. Sounds simple enough, but for whatever reason it just wasn’t obvious to me. I ended up powering through my “review” in one extended session because I was afraid I’d lose my place. The archetype itself was impressive. It’s clear from the information and detail that people have spent a lot of time and effort developing the adverse reaction archetype. There’s no question that a lot of great minds had been involved in this work. The definition made sense as did the data that was being collected and presented. The archetype offered flexibility for information gathering that included the simplest form of adverse reaction to complex re-exposure and absolute contraindication notation (this is sorely missing in many systems I’ve used over my career). Overall I had little insight to offer during the review, only a couple of minor comments.

I’d say the entire process was pretty straightforward with some minor complications. Like everything else I’m sure the process would get easier over time and multiple uses.

Thanks Jerry. Your independent and honest opinion is much valued. Perhaps next time... !! (Just joking)

Preserving health data integrity

How valuable do we really think health data is? How seriously do we take our responsibility to preserve the integrity of our health data? Probably not nearly as much as we should.

Consider the current situation of most clinicians or organisations when purchasing a clinical EHR system. What do they look for? Many possible answers are obvious, but there is one question that I suspect very few are asking. How many consider what data they will be able to export and convert to another format, preserving the current data integrity, at the end of the typical 5-10 year life span of the application? Am I wrong if I suggest it is not many at all?

Despite all the effort that we clinicians put into entering detailed data to create a quality health record we don't seem to often consider the " What next?" scenario. How much and precisely what data will we be able to safely extract, export, transfer or convert into the next, inevitable, clinical system? Ironically, we are simultaneously well aware that clinical systems have a limited technical life span.

Any and all of the health data in a health record is an incredibly valuable asset to the holder, to the patient (if these are not the same entities) and to those downstream with whom we may share it in the future - in terms of $$ invested; manpower resources used to capture, store, classify, update and maintain it; and not least the future value that comes from appropriate and safe clinical decisions being made upon the integrity of existing EHR data.

Yet we don't seem to consider it much... yet. However, as more clinicians are creating increasing amounts of isolated pockets of health data, we should be thinking about it very hard.

Every time we change systems we put our health data at risk - risk of absolute data loss and risk of possible corruption during the conversion. The integrity of health data cannot be guaranteed each time it is ported into a new system because current methods always require some kind of intervention - mapping, transformations, tweaking, 'cleaning', etc. Small errors can creep in with each data manipulation and which over time, can compromise the safety and value of our health data. On principle we know that the data should not be manipulated, but being limited by our traditional approach to siloed EHR applications, we have previously had little choice.

We need to change our approach and preserve the integrity of our health data at all costs. After all it is the only reason why we record any facts or activity in an electronic health record - so we can use the data for direct patient care; share & exchange the data; aggregate and analyse the data, and use the data as the basis for clinical decision support.

We need to change our approach and preserve the integrity of our health data at all costs. After all it is the only reason why we record any facts or activity in an electronic health record - so we can use the data for direct patient care; share & exchange the data; aggregate and analyse the data, and use the data as the basis for clinical decision support.

We should not be focused on the application alone.

Apps will come and go, but we want our health data to persist - accurate and safe for clinical use - beyond the life span of any one clinical software application.

I've said this before, but it's worth saying many times over:

It's. all. about. the. data.

One of the key benefits of the openEHR paradigm is that the data specifications (the archetypes) are defined independently of any specific clinical system or application; are based on an open EHR architecture specification; and are publicly available in repositories such as the Clinical Knowledge Manager. It means that any data that is captured according to the archetype specification is directly usable by any and all archetype-compliant systems. Plus the data is no longer hard-wired into a proprietary application so that it is orders of magnitude easier to accurately share or transfer health data than it has before.

Clinical system vendors that don't directly embrace the archetype-technology may still 'archetype-aware', and can choose to use the archetype specifications as a means to understand the meaning of existing archetyped data and integrate it appropriately into their systems. Similarly they can map from their non-openEHR systems to the archetype specifications as a standardised method for data export and exchange.

The openEHR paradigm enables potential for archetype-compliant systems to share the same archetyped data repository - along the lines of an Apple platform 'plug & play' approach, with applications being added, removed or updated to suit the needs of the end-users, while the data persists intact. No more data conversions needed.

Adapted from Martin van der Meer, 2009

Now that's good news for our health data.