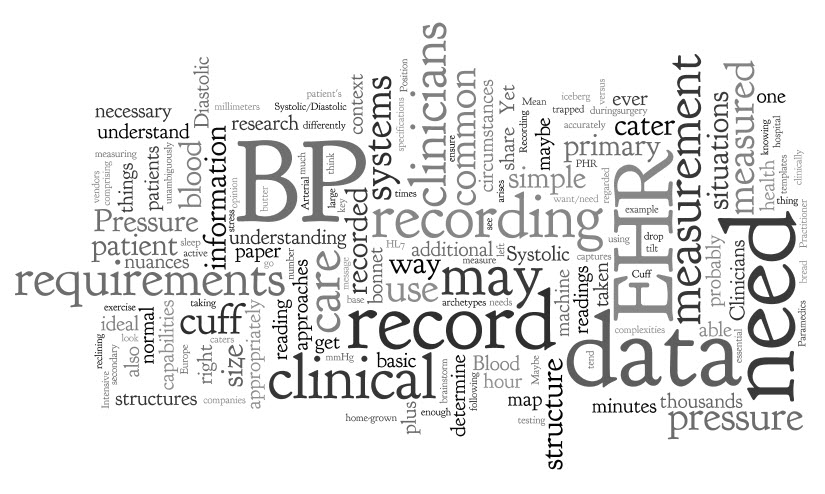

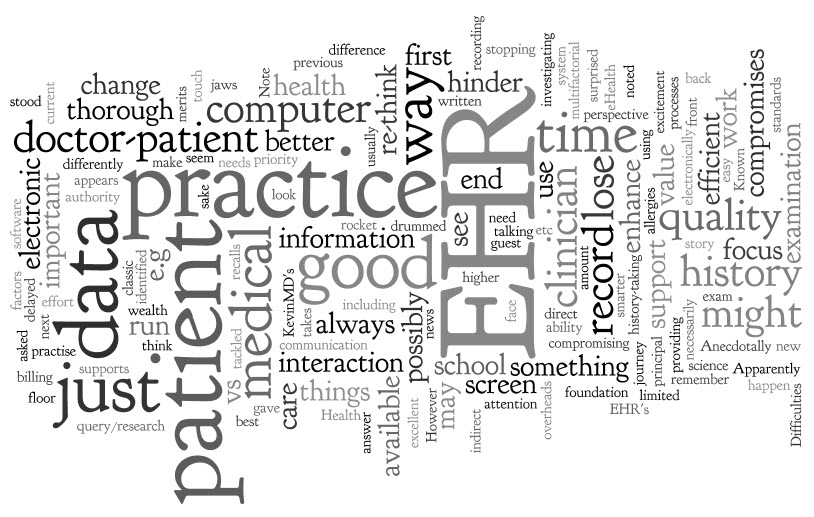

Clinicians record their findings and conclusions remarkably efficiently on paper, recording the contextual variations succinctly and in a way that other clinicians can understand. Getting computers to do the same thing – to enable clinicians to record simply in the normal circumstances, but be able to cope with the complex and detailed where it is critically needed - is not a trivial task. Ensuring that a user interface reflects a clinician's work flow and captures the evolving requirements in a clinical consultation is extremely complex. Obviously computers are not as flexible as a human brain; they can only record what is pre-ordained in their programming.

We clinicians should expect our electronic health record (EHR) applications to do be able to support our recording requirements and work flow however, in reality, there are very few clinical systems that do this well.

Clinicians record their findings and conclusions remarkably efficiently on paper, recording the contextual variations succinctly and in a way that other clinicians can understand. Getting computers to do the same thing – to enable clinicians to record simply in the normal circumstances, but be able to cope with the complex and detailed where it is critically needed - is not a trivial task. Ensuring that a user interface reflects a clinician's work flow and captures the evolving requirements in a clinical consultation is extremely complex. Obviously computers are not as flexible as a human brain; they can only record what is pre-ordained in their programming.

We clinicians should expect our electronic health record (EHR) applications to do be able to support our recording requirements and work flow however, in reality, there are very few clinical systems that do this well.

Identifying recurring patterns in clinical practice help to ensure our EHRs can record health information effectively. When we look closely, clinical medicine is fractal in nature.

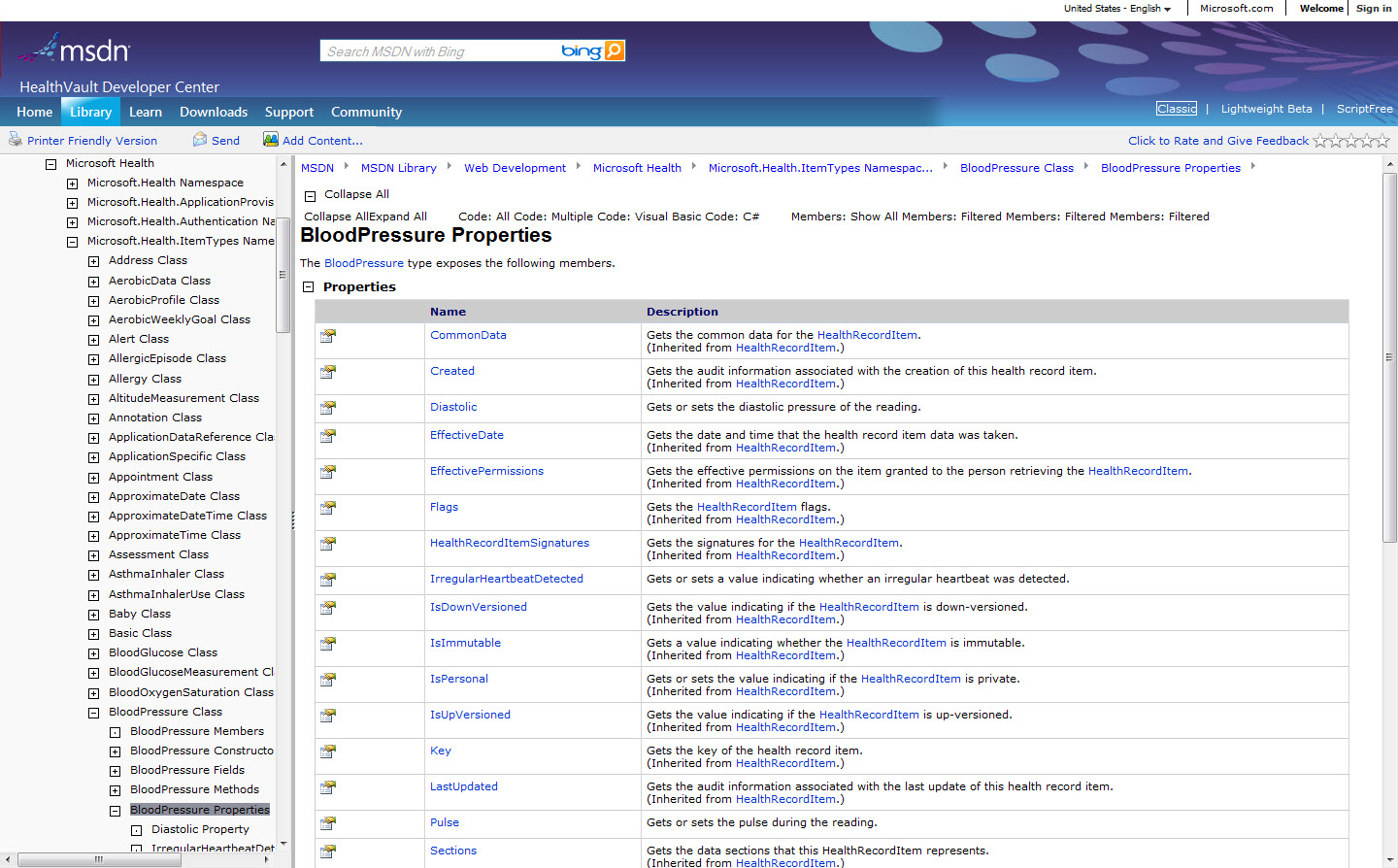

What do we have to record, display, query and exchange in our EHRs? Lots of measurements such as Pulse, Temperature, Blood gases, Apgar Score, Height, and Weight are pretty straightforward. Those screens are a breeze - type in a couple of numbers and hit 'Save'. Evaluations, diagnoses and assessments are also pretty uncomplicated.

However it starts to get much more complicated when we start to explore history-taking and examination findings - where the bulk of the 'art of medicine' takes place.

Let's think of the evolving nature of a typical clinical consultation. It would be so nice if each patient walked into my consulting room with a single, neatly packaged problem for me to solve, but this is not the norm. In fact the majority arrive with the dreaded 'shopping list or, worse still, with multiple problems that are gradually revealed one by one throughout the consultation. So while computers will capture a linear work flow really well, the typical patient consultation is anything but linear.

But each of these problems will likely be recorded in a common pattern - reason for encounter, history of presenting complaint, systematic questioning, examination, differential diagnosis, investigations, diagnosis, management plan and follow-up.

Consider a simple skin examination. The clinician inspects the patient's back and finds an abnormality - a dark, warty lesion. They record its location, dimensions, shape, regularity, surrounding skin etc, and - oh oh - that there is an area within it with increased pigmentation. Then they focus on the hyperpigmented area - recording location, dimensions, shape, surrounding tissue etc. Then they take a photo for future reference and pull out the dermatoscope - recording yet again the location, dimensions, shape, surrounding tissue etc. There are repeating patterns identified here at increasing levels of granularity.

Recently I've been modeling the examination of the hand. Easy, I thought... at first. OK, we’ll use the general clinical principles to record inspection and palpation of the hand as a whole, including specific hand-related items such as presence of Duypuytren’s contracture, wasting of lumbricals plus circulation, sensation (pinprick, temperature, vibration etc), and strength. Then we need to potentially be able to examine in detail:

- per named finger – again inspection and palpation per digit, plus circulation, sensation, movement of each joint on that finger

- per named nerve eg median nerve distribution

- per named tendon

- per named joint – inspection, palpation and movement of each joint

- per named bone - palpation

And if we found something on inspection of the finger such as a nodule, we need to be able to inspect and palpate the nodule. And if there was a pigmented part of the nodule we'd be documenting it in a similar way to the wart on the back - inspect the pigmentation in detail, including an image of it for future reference. These are incredibly complex recording requirements.

Which way we view or prioritize these requirements will depend on the patient context and the expertise of the examiner. For example, recording needs for a hand examination by a General Practitioner will differ from that of a Rheumatologist or an Orthopaedic Surgeon. Consider also the plastic surgeon about to take a patient to surgery to repair a severed finger will absolutely need to be able to record a detailed breadth and depth of not only the hand and the finger but the digital vessels and nerves that will need their expert attention.

Do you get a sense of the fractal nature of medicine? Repeating patterns in the way we record health information:

- revealed as we repeat the work flow of a typical history and examination process; and

- revealed as we record our findings in more and more detail.

Content modeling for EHRs needs to reflect the fractal nature of clinical medicine accurately, both coarse and fine levels of granularity, and ensuring that the data capture is ‘fit for clinical purpose’.

Inspired by @samheard, as usual;-)

I spent a total of 19 weeks living away from family in London during 2007. Much of that time was spent by myself, and I ended up walking and exploring - the main task being to locate Banksy pieces. It really started just as something to do to keep me active and to soak up the essence of a different city. Armed with a Banksy Walking Guide that I bought on eBay, I set out on a number of days and walked for miles, finding many stencils around the East End. Some had been buffed; some were hidden behind fences; some just sitting there just like the picture in the book.

I spent a total of 19 weeks living away from family in London during 2007. Much of that time was spent by myself, and I ended up walking and exploring - the main task being to locate Banksy pieces. It really started just as something to do to keep me active and to soak up the essence of a different city. Armed with a Banksy Walking Guide that I bought on eBay, I set out on a number of days and walked for miles, finding many stencils around the East End. Some had been buffed; some were hidden behind fences; some just sitting there just like the picture in the book.